A titan of tech and industrial innovation has been laid low by a mere speck of dust. Last week, Apple quietly announced that they were extending the warranty on their flagship laptop’s keyboard to four years. As it turns out, the initial run of these keyboards, described by Jony Ive as thin, precise, and “sturdy,” has been magnificently prone to failure.

The Timeline

- March, 2015: Apple introduces butterfly keys in the 2015 MacBook

- October, 2016: Apple introduces butterfly 2.0 in the Late 2016 MacBook Pro. We note in our teardown, “The keycaps are a little taller at the edges, making keys easier to find with your fingers. The switches have likewise gained some heft.”

- Late 2017: Keyboard complaints begin to roll in

- June 2018: Apple announces keyboard replacement program

The first-gen butterfly keyboard showed up in 2015, but the real root of the problem dates back to 2012 in the very first Retina MacBook Pro. That radical redesign replaced their rugged, modular workhorse with a slimmed-down frame and first-of-its-kind retina display.

And a battery glued to the keyboard.

The new notebook was universally applauded by tech pundits, with one notable exception: my team at iFixit. Unlike the rest of the tech media, we don’t judge products for their release-day usability or aesthetics—we focus on what will happen when the device (inevitably) fails. How time-consuming (and therefore expensive) is it to open? Can broken components be replaced individually, or will you have to swap out more expensive larger modules? Our score provides a consumer with an educated guess of repair costs before they buy the product.

In our eyes, the new design was a repairability flop. We downgraded Apple from a seven-out-of-ten to a two. The subsequent 2013 update sent the MacBook line into a freefall, earning a mere 1/10—the lowest a notebook had ever earned at that point. They haven’t recovered since.

Apple has shipped two iterations of the butterfly mechanism. The 2.0 variant seems to handle dust a bit better, but had been on the market for a year before the volume of complaints reached a fever pitch. Anyone who has paid Apple to swap out their upper case in the last two years has most likely gotten the newer design. As far as we know, Apple’s new warranty replacements are unchanged—if they had improved, you’d think Apple would mention it—but we haven’t analyzed any units that have shipped in the last few weeks. (If we can get our hands on one, I’ll update this.)

No Margin for Error

The basic flaw is that these ultra-thin keys are easily paralyzed by particulate matter. Dust can block the keycap from pressing the switch, or disable the return mechanism. I’ll show you how in a minute.

The heroine at the center of this story is Casey Johnston, an editor for The Outline who has reported extensively on this issue since her computer came down with the affliction last year. Her research found that “while some keys can be very delicately removed, the spacebar breaks every single time anyone, including a professional, tries to remove it.”

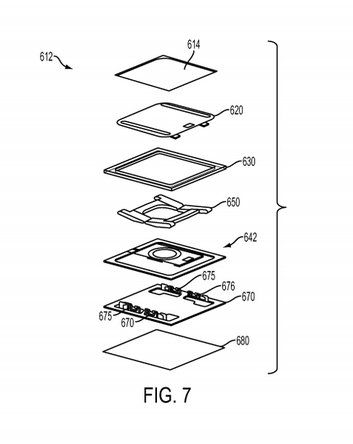

So you can’t switch key caps. And it gets worse. The keyboard itself can’t simply be swapped out. You can’t even swap out the upper case containing the keyboard on its own. You also have to replace the glued-in battery, trackpad, and speakers at the same time. For Apple’s service team, the entire upper half of the laptop is a single component. That’s why Apple has been charging through the nose and taking forever on these repairs. And that’s why it’s such a big deal—for customers and for shareholders—that Apple is extending the warranty. It’s a damned expensive way to dust a laptop.

Let’s take a look and see what’s actually going on. We put a keycap under a microscope and injected a grain of sand so you can see how this happens. The grain is in the bottom right corner, and it’s completely blocking the key press action. It’s very challenging to remove it with compressed air.

The particle wedges underneath the butterfly lever, preventing it from depressing. With the space bar, there’s virtually no way to remove the key cap without destroying the key. And since the keyboard is part of the monolithic upper case, a single mote can render the computer useless.

The particle wedges underneath the butterfly lever, preventing it from depressing. With the space bar, there’s virtually no way to remove the key cap without destroying the key. And since the keyboard is part of the monolithic upper case, a single mote can render the computer useless.

Traditional key caps are more resilient to dust, and can be removed and individually repaired as necessary. But of course, they’re not 40% thinner.

Thin may be in, but it has tradeoffs. Ask any Touch Bar owner if they would trade a tenth of a millimeter for a more reliable keyboard. No one who has followed this Apple support document instructing them to shake their laptop at a 75 degree angle and spray their keyboard with air in a precise zig-zag pattern will quibble over a slightly thicker design.

This is design anorexia: making a product slimmer and slimmer at the cost of usefulness, functionality, serviceability, and the environment.

A repairable pro laptop is not an unreasonable ask. Apple has a history of great keyboards—they know how to make them. There are very successful laptop manufacturers who consistently earn 10/10 on our repairability scale. Apple fans are already making noise about the dearth of new Macs, especially upgradable options for professionals. Fortunately, Apple seems to be listening with their new warranty program.

Which brings us back to the point. Why did it take so long, and so many complaints, for the repair program to be put in place? Why do you need to send your MacBook Pro away for upwards of a week for a repair? That’s easy: because Apple made their product hard for them to repair, too. Apple’s new warranty program is going to cost them a lot of money.

Apple’s profit on every machine that they warranty under this new program has been decimated. There is a real business impact caused by unrepairable product design. Samsung recently had a similar experience with the Note7. Yes, the battery problem was a manufacturing defect. But if the battery had been easy to replace, they could have recalled just the batteries instead of the entire phone. It was a $5 billion design mistake.

But this isn’t just about warranty cost—there is a loud outcry for reliable, long-lasting, upgradeable machines. Just look at the market demand for the six-year-old 2012 MacBook Pro—the last fully upgradeable notebook Apple made. I use one myself, and I love it.

Apple can do better. Let’s start with a slightly thicker, more robust keyboard. Butterfly 3.0, we’re waiting for you.

In the meantime, let’s give some other companies a shot. Dell and HP have gorgeous, reliable, repairable flagship laptops that are getting rave reviews. Right now, I think they’ve done more to earn your business than Apple has.

10 Comments

I took my MacBook Retina, 12-inch, 2017 to the downtown Palo Alto store for exactly this problem in May of 2019 (i.e. several keys sometimes not working, sometimes doubling-up on the character). The Genius Bar rep first suggested I’d spilled liquid on the keypad (I had not), then took it, cleaned it, and found the problem still persisted. The store kept the system for servicing, then called the next day to say they couldn’t fix the problem and needed to send it to a service center. Three days later I got the system back - now working properly. HOWEVER they claimed the problem was fixed by “reseating a connector” - and hit me with a bill for $575 since the product was now “out of warranty”. If the problem was as simple as stated, why did it need to go to a special repair center for three days? This seems like an effort to evade responsibility for the known, admitted keypad problem. MOREOVER, the above Apple webpage dedicated to this issue now states the warranty period is NOT extended beyond the original.

Bill - Reply Share

Unfortunately, Apple’s keyboard warranty does not cover all Macs, which is extremely frustrating. I’ve tried the fixes here and somehow got the key unstuck.

carl janes - Reply Share

How much does it cost to get it replaced?

Daniel John - Reply Share

“How much does it cost to get it replaced? “

The keyboard assembly is part of the upper frame casing, it involves getting that part and the battery unless you want the technician to remove the old battery which can take an hour of extra time to accomplish. New upper palm wrests with working keyboards for the 13 inch mac book pro cost about $240 plus the 2 hours of labor removing components from the old frame and putting it in the new frame. A fair technician with decent skills should charge about $160 for the labor, so total cost for a working keyboard should be around $400.00. Some forum posts about this repair by apple put the price at $550 to $650.

service - Reply Share

Just picked up my MBP 2016 (Touchbar) from the Apple store after my weeklong free repair. The keyboard is new and I got a new battery and probably other components replaced as well. The receipt shows the repair would have cost $493 but was free because it was under the extended warranty. I’m thrilled at this because it cost Apple a lot of money and hopefully the more people that do this will convince them to stop making amazing machines that absolutely suck to repair. The essentially new computer isn’t too bad either. :P

Abe Snider - Reply Share