Until two years ago, Father’s Day was a breeze. My dad took no pleasure in the trappings of consumer holiday culture, so I never had to rush out for a golf-themed necktie or “World’s Greatest Dad” coffee mug. Buying any sort of gift—even spending pocket change on a greeting card—was, to my dad, a superfluous gesture. He never wanted anything, and preferred receiving nothing but a bit of time and attention. A visit by me or my brothers brought him the most joy. Barring that, a phone call home from wherever I happened to be in the world at the time was Father’s Day gift enough for him.

Anyone who knew him could tell that dad was never into things. He was a die-hard minimalist before it was a trendy lifestyle choice. Stuff to him was just that: stuff. In his view, matter just got in the way of what really mattered—a conversation around the dinner table, an afternoon sharing beers and stories on the back porch.

This preference for the non-material made things easier on the rest of the family when he finally lost a long battle with cancer two springs ago. After the death of a loved one, a purging of possessions ensues. Step one is a cataloguing of belongings. What’s left behind tells a lot about someone. Dad didn’t leave us much to sort through. Besides a few sets of clothing, his bedroom closet contained a single box of keepsakes: a few high school yearbooks, some yellowed newspaper clippings, a handful of old photos. Other than a small shelf of books in the living room and a shoe shine kit stashed in a kitchen cupboard, nothing else in the house really belonged to him.

Then there was the garage, home to his toolbox and his old bicycle. Dad bought the bike during the 1980s bike boom, when high-quality Japanese bicycles flooded the domestic market, making good bikes affordable to the average American. Ever practical in his purchases, he opted for a Nishiki Century, an economically-priced, well-built road bike. I remember him riding it, not for pleasure, but as one leg of his daily commute.

In his work clothes and steel-toed shoes, dad would ride the Nishiki five or so miles down to the freeway on-ramp where his workmate would pull off the freeway long enough for him to jump in the car for the rest of the ride down to San Pedro where he worked as a mechanic for the Department of Water and Power. The Nishiki would sit chained to a pole until its return trip home at the end of the work day.

For my dad, his bike was a tool. He kept it in good working order—but it was a means to an end, not an object in itself to be appreciated aesthetically or fawned over.

After the sorting, one of my brothers took dad’s high school class ring. The other took his pocket knife. I took the old Nishiki.

Grieving is a weird process, and part of mine involved spending time with that old bike. The thing was a mess. The tires were brittle and crumbling, spokes askew, rims warped. All the shiny bits were coated in rust. The headset was seized as the packing grease had petrified into a crust. Spiderwebs shrouded every nook and cranny. It looked ready for the junk heap; it hadn’t been touched in nearly 30 years.

First, I took the whole thing apart. Broke it down completely. All the way down to the ball bearings in the bottom bracket. Then I cleaned and lubed everything meticulously and put it all back together. Rebuilding the bike piece by piece, replacing any parts like cables and brake pads that were beyond repair.

This laborious process gave me time alone, in the garage, late at night after the day’s work and hustle and bustle, after my own kids were finally tucked in and the house was finally still. It took the better part of a month. It was dirty, physical work—but quiet. In no rush and with no deadline, I took all the time I needed, spending hours on tiny details, working a rag and metal polish over the quill stem and crank arms until I could make out my reflection.

When someone close passes, there are a million things that need to be attended to. Logistics, notifying friends far and near, dealing with condolences, putting on a brave face. Attending to the emotional needs of others just as profoundly impacted by the loss. My mom took it hard. Those late nights in the garage, alone in the quiet, gave me time to work out my own grief, away from others I had to be strong for.

Once the bike was back together, I took it for a spin. What I thought would be a quick shake-down ride turned into a meandering tour amongst the beautiful morros of the Central Coast here in California. Anyone seeing me whiz by would have blamed the brisk wind in my eyes for the tears streaking my cheeks.

I have my dad’s hairline, his lanky frame, his big feet, and his minimalist tendencies. Clutter is my nemesis. But I do hang on fiercely to a few possessions that are laden with meaning. Dad’s bike is one of them.

When I can, I take it for rides when I miss him. It is an object that connects across distances you can’t plot on a map or measure with GPS.

In my work at iFixit, I spend a lot of time thinking about repair. We can easily focus too narrowly on the nuts and bolts of repair without pulling back and looking at the bigger picture. Fixing dad’s bike reminded me that repair is not solely a utilitarian exertion. It can be a way we work things out—personally, socially, even emotionally.

Making a commitment to fix something goes much deeper than just saving a few bucks or minimizing waste. These are all noble aims, of course, which I believe are immensely important in today’s world. But, for me, the act of repair can help us fix much more than a throwaway economy, overflowing landfills, and a poisoned environment.

Repair can be a meditative practice, opening a space for introspection, a much-needed pause in the daily grind to reflect on why we do what we do—and feel how we feel. Repair, as I was reminded laboring alone in the garage elbows deep in grease, connects us to others—even those who came before and are no longer.

Repair speaks to me personally because it is fundamentally an act of caring. It is an exercise in compassion, and therefore makes us more human. When you restore something to working order, you are resurrecting more than just stuff. You are keeping alive a host of intangibles associated with those objects: memories, relationships, significance, history.

Repair is restorative. By taking the time and energy to fix something that is broken, repair is a way of making things right in the world, if only on a micro-scale.

Dad’s bike isn’t anything special to look at. A low-level Nishiki, one of millions produced during the bike boom of the 80’s. I can’t imagine it meant very much to him. But it means the world to me. And, I’m proud to say, it works just as well today as it did the day he bought it.

8 Comments

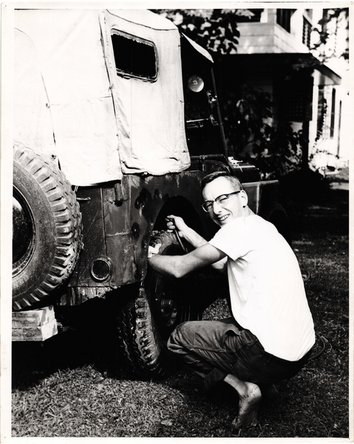

It’s not a JEEP in the first photo. It’s a Series Land Rover. NICE!

CB3LazyBW - Reply

Marty,

Awesome, My dad always wore coveralls when working. I have his last pair all stained and thread bare hanging in my closet in a dry clean bag. He gave my wife his Hockey jacket which he played from grade school until his mid 60’s. It hangs in her closet. Both lift my spirits every time I see them.

Thank You,

Michael

Michael Jerome Hennessey - Reply

I enjoy reading this Text,I'm thinking about my father's bike waiting in the shed.

Regards Andreas

Andreas Gailler - Reply

NISHIKI… my first new 10-spd bike. Purchased from a hole-in-the-wall bicycle shop in Seattle!! It must have meant something to him to hang onto it for so long - just waiting for the “kid” to enjoy it some day. :)

mwold - Reply

I did the same thing to my dad’s bike when he died. He wanted my daughter to have it, so I cleaned it all up, re-greased all the bearings and put new tires on it. My daughter is proud to ride it.

gerrycud - Reply